How Wenger and his staff brought unprecedented glory to Gunners

The French coach’s early awareness about the importance of specialists created a legacy beyond trophies…

The summer of 1996 was heaven for football fans in England thanks to the Euros that welcomed the beautiful game “back home”. Three Lions displayed their best performance in thirty years at a major tournament and reached the semi-finals only to be beaten by Germany on penalties. Public opinion was divided between feelings of achievement and failure. Presumably, it was both, since Euro 96 revealed both the breakthrough and limits of English football at the time.

On the upside, Premier League, only four years old, seemed a huge success both on and off the pitch, celebrating the multinational world of football and providing the national team with quality players. Together with global audiences and money flooded in talents from all around the globe. On the downside, despite being unchained from many local drawbacks, English game was yet to incorporate the multilateral expertise of foreign managers.

There were three of them before Wenger but none created a significant impact: Journeyman Josef Venglos couldn’t overcome a culture clash at Villa despite his innovative ideas, while Ossie Ardiles and Ruud Gullit offered entertainment but lacked results at Spurs and Chelsea, respectively.

This is why a guy looking more like a school principal rather than your regular football coach was received with doubt rather than a warm welcome. The London Evening Standard’s headline “Arsène Who?” has now become a part of football folklore, but given the record and scarcity of former examples, it probably wasn’t as hostile or xenophobic as is perceived today.

Born and bred in Duttlenheim, Alsace, Arsène Wenger was not actually a no-name manager. He had done well in Monaco reaching the final of the Cup Winners’ Cup in 1991-92, but was almost forgotten in the Far East, after leaving for Japanese club Nagoya Grampus to overcome the trauma of a match-fixing scandal involving Olympique Marseille that cost him league titles in France. His reception as a low-key manager owed more to British ignorance about foreign coaches than his actual profile. Nevertheless, “first-ever Arsenal manager born outside the UK” did not sound assuring to suspicious minds. He had to build fast and well.

Boring on the pitch, untidy off it

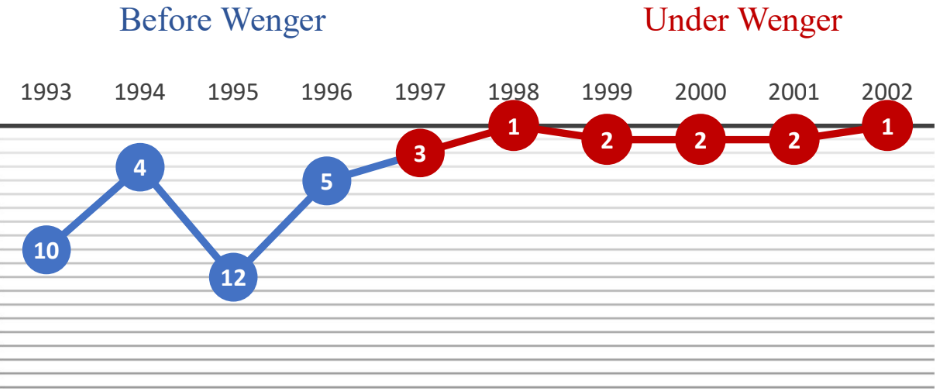

The Gunners, meanwhile, were trying to shake off their “Boring, boring Arsenal” tag but didn’t really seem to know how. Despite two First Division titles in 1988-89 and 1990-91, the club hardly pleased their fans and was looking somewhat outdated in the new Premier League era. Inconsistency had become the norm. In the last five seasons before Wenger, Arsenal came fourth, tenth, fourth, twelfth and fifth, respectively. Locked in a kind of purgatory, they were neither good enough for title challenge nor bad enough to give it up completely. Then there was a striking indifference to the requirements of the modern game.

At least this is what defensive midfielder Rémi Garde saw when he signed for the club at the beginning of the 1996-97 season. He was the first signing of Wenger era; in fact, he arrived before the coach who recommended his transfer all the way from Japan. According to Xavier Rivoire’s Arsène Wenger: The Authorised Biography, when Garde entered Gunners dressing room for the first time, he was shocked at the sight of a candy jar, casually sitting on a table for common use. Everyone, in turn, took their bit at will. Garde was used for cornflakes and energy drinks in France, where players were not allowed to consume such sugary food. Such a lack of awareness in terms of diet and hygiene was striking for a continental player. And it wasn’t only about eating whatever they found. Drinking was an even bigger problem.

Perspectivism: European and Japanese Wengers

Fortunately, Wenger had a plan and the almost unconditional support of Vice-chairman David Dein. And despite looking like a school principal, he was a great student, having learned his trade in France and Japan. Indeed, this double perspective acquired in the West and East provided him with a rare dual character.

“French” or rather “Alsatian” Wenger was a die-hard idealist who feared a heart attack on the bench after every game lost. “Japanese” Wenger, in turn, was much more mature, having seen the ups and downs of life and careers. By the time he arrived in London, he was no more a coach known for impulsive interventions. He had learnt to leave some problems to time.

Garde, who knew his coach from France, realised this change in his attitude. Arsène was now like an iron fist in a soft glove. He gradually instilled a more European, more French approach. And “gradually” was the keyword, because, since day one, Wenger made everyone sure he was not in London to leave soon. More importantly, he assured experienced players that they would stay too. This psychological support was as important as technical or scientific interventions for the extension of careers of elder players such as David Seaman, Martin Keown or Tony Adams. “He did not remove the jars overnight and did not make a scene upon finding them,” Garde said. Instead, he sought advice from his dietician, who told players the harms of sugar to end such and similar habits.

The squad, however, wasn’t that sure. As a team not short of unprofessional professionals, Arsenal players mostly shared the scepticism of English press about the new manager. The “establishment” seemed comfortable with the disorderly order and any challenge to the status quo raised eyebrows. As Tony Adams admits, players were afraid of change but still expectant about what the new coach would bring in.

And Adams was one of the most troubled due to his drinking problems. Wenger talked to him right away and made sure he wanted the captain to become the player he could, leaving unpleasant habits aside. He went personal, too. Young Wenger had grown up in Duttlenheim wandering around in the pub of his family, witnessing how alcohol could ruin lives. This sincere communication was crucial for convincing his captain.

Still, things weren’t rosy right away. The first Premier League game of Wenger’s Arsenal career was against Blackburn at Ewood Park. After the 2-0 victory, on the way back home, players in the team bus began to sing: “We want our chocolate back!” But he would not allow for counter-revolution. No cacao, chocolate or other confectionery was allowed in Gunners locker room anymore.

As the anecdote above shows, however, you need results to install your manners. Without his wit on the pitch, Wenger could have never instilled his window off it. Especially for a coach without a top-level playing career, he needed to prove his worth.

Arsenal league positions in the first ten seasons of PL

You play what you eat

And the right methodology required the right people. Wenger was always adept at gathering experts and sticking with them. He either brought along or was endowed with key backroom staff upon his arrival. In addition to more conventional positions such as assistant manager (Pat Rice, Boro Primorac), head of youth development (Liam Brady) and chief scout (Damien Comolli), he appointed some unusual figures with unusual titles such as dietician Yann Rougier, osteopath Philippe Boixel and “freelance” fitness coach Tiburce Darrou, who helped the club from France.

Incorporation of such expertise was crucial to make a difference. Recovery, nourishment and self-care were a kind of holy trinity for Wenger, not less important than his tactical approach and fluid 4-4-2 on the pitch. But it also required proper distribution of tasks in order to ensure harmony. Indeed, he sought a peaceful hierarchy not only among players but also among staff. And to instil confidence, he often trusted in statistics and expertise provided by others at the expense of his own convictions.

Wenger’s approach to diet has become particularly famous because of its innovative character and his meticulousness about it. Dr. Yann Rougier, the nutritional biology specialist who worked with the coach almost 25 years including his tenure in London, was a kind of soulmate to Wenger, believing diet and food hygiene can have an impact of 15 to 20 per cent on the performance of a top athlete. He was always impressed with how Wenger combined human, technical and scientific aspects of coaching in his quest for perfection.

Wenger’s sojourn in Japan was influential in dietary terms as well. Surprised at the rarity of obesity in Far East, he gradually introduced rice, vegetables and fish to menu of club cafeteria. Fried chicken and other fried dish were removed, to be replaced by broccoli with chicken. And his regime was not restricted with club facilities. Rougier compiled a diet file for each player and applied a customised policy depending on individual characteristics. Newcomers were asked about their lifestyle for a tailored diet. Besides, for away games, Wenger and Rougier determined what players would eat at airports, hotels or on plane. The coach took his rigour to new levels by preventing players even from drinking cold water.

He also needed some guile to make sure their recipes were followed. For instance, morning trainings were scheduled for 10.45 a.m. so players stay at facilities for lunch and eat the right food.

Diet was complemented with other medical and nutritional experts, such as osteopath or Philippe Boixel, who helped moulding the best training regime for each player. Osteopathy, a discipline of alternative medicine focusing on muscle tissues and bones, aimed at instilling a holistic approach to body, finding connections between, say, a muscle pain and dental infections and cured one to heal both. One of the strengths of Wenger was his so-called eclectic approach that combined conventional science with new techniques. He also had Tiburce Darrou, the fitness coach back in France, who treated injured Arsenal players for a faster and more solid recovery.

Transfers

Chief scout and head of transfer committee Damien Comolli was another key figure, for Wenger was always extremely careful about transfers. He knew that a poor signing can cost a manager his job. Along with Garde, the club signed Patrick Vieira for €5.35 m from Milan in the summer of 1996 through mediation of Wenger. During winter transfer window, he brought teenager Nicolas Anelka from PSG for just €760,000. These shrewd moves were key for early success. Having come to club in October, Wenger finished the season third behind Manchester United and Newcastle. In 1997-98, his first full season, The Gunners won the title in style. The glory would clear the path for Wenger for further innovations.

And his experience at Nagoya Grampus was not only about acquiring an Eastern perspective. Japanese owners had given him opportunity to build a club from scratch, including the creation of a new training centre, which he would apply once again at Arsenal for creation of the new Colney facilities completed in 1999. The state-of-the-art training centre would yield further glory to club, including the unforgettable “Invincibles” tag when Arsenal won Premier League without a single game lost in 2003-04.

Legacy

Continued success can create an illusion of endlessness. This is probably why Wenger’s last seasons in London were often seen as a failure despite consistent participation in UEFA Champions League. Still, his legacy is far beyond trophies and league positions.

For Wenger, football was a noble discipline of humanities. Probably his deepest impact was psychological. Often introvert and ignorant about foreign managers until millennium, English football learned to trust in unknown minds. If it hadn’t been for Wenger, what Jürgen Klopp, Pep Guardiola and Thomas Tuchel are doing today would be hardly imaginable. And it wasn’t only about granting time for idealists so they can build success. Pragmatists such as Mourinho, Ancelotti, Conte, Scolari, Mancini also enjoyed the same comfort. So much so that an English manager is yet to win the Premier League, which is now 30 years old.

Post-war longest managerial reigns in England

| Sir Alex Ferguson | Manchester United | 1986-2013 (26 years) |

|---|---|---|

| Matt Busby | Manchester United | 1945-1969 (23 years) |

| Arsène Wenger | Arsenal | 1996-2018 (21 years) |

| Brian Clough | Nottingham Forest | 1975-1993 (18 years) |

| Ted Bates | Southampton | 1955-1973 (18 years) |

Wenger’s crowded staff looked extravagant and arrogant back in 1996, but it turned out to be a prerequisite for success and organisation at top level. Without such diversified expertise and task distribution, he could have never competed with Manchester United or created a team that continues to inspire a generation of coaches and football fans all around the globe.

This case-study is developed solely as the basis for class discussion. Cases are not intended to serve as endorsements, sources of primary data, or illustrations of effective or ineffective management.