“I wanted to go back and start a project there. I wanted to do something for the country and to use football—everyone loves football there—as a means to educate kids. . . . We tell them how hard it is to become a professional footballer. Perhaps only one or two will succeed. That’s why their education matters.” – Patrick Vieira, Co-founder of the Diambars Institute and Former Football Player

The globalized world shrinks distances and renders intercontinental travel and interactions easier than ever. Such ease comes with its great advantages alongside major responsibilities. It certainly has its implications on the world of sportive competition, especially football. Nowadays, clubs, managers, and coaches are not only able to engage in transfers from established clubs and their near geographic area but are also able to scout talents from different parts of the world and train them to find the next football superstar. Africa has been a hub for such scouting and training activities for the past 40 years. However, the process has not always been so altruistic and humanitarian.

In the era that preceded the FIFA regulations that set boundaries and clear rules for the scouting and transfer of young talent from Africa to Europe, there have been instances of poaching and child trafficking that left children, away from their families, with no foreseeable future. A UN report from 1999 drew attention to the “danger of effectively creating a modern-day ‘slave trade’ in young African footballers.” The criticism, active discussion, and efforts to remedy the problem led to regulations that strictly prohibited the transfer of underage players and introduced other measures for the protection of such players, their families, and other associated entities.

The era of structured and organized talent academies

The instating of the regulations led to the foundation and operation of structured, organized, and regulated talent academies. Some of these academies like ASEC Mimosas in Cote d’Ivoire are founded and run by African clubs or associations, some like West African Football Academy (Feyenoord) in Ghana by a coalition of African and European entities, and some like Pepsi Football Academy in Nigeria, by private corporations. There are also non-affiliated academies that are, for the most part, poorly designed and run. The successful and notable academies include Diambars Insitute in Senegal, Midas Football Academy in DR. Congo, Right to Dream Academy in Ghana, Kadji Sports Academy in Cameroon, and l’Academie Jean-Marc Guillou in Mali, just to name a few.

These academies scout young talent from varied age groups and provide them with athletic and academic training and education. The young adults who have been trained in such academies remain on the radar of coaches and managers from around the world. Some of these clubs are endorsed or run by clubs in Europe like Metz, AS Monaco, Ajax Amsterdam, Athletico Madrid, PSG, and Olympique de Marseille, which means that those clubs oversee the education and development of the young athletes and get the chance to offer them positions in their teams when they come to the legal age of transfer before other clubs do. While some see this as an opportunity for growth, income, and development both on the individual/family level and on the level of development of countries of these talents, others criticize the practice claiming that it contributes to the drain of talent and skill from the continent stagnating the development.

“Our boys and girls are passionate about STEM subjects and can feed that section of Ghanaian society afterward” – Tom Vernon, founder of Right to Dream and former head scout for Manchester United

Academics and social change

The good thing is that some of the clubs acknowledge the challenges of working in the complex situation they are in and they attempt to situate themselves accordingly to provide holistic education and experience to the youth they are working with. Academies like Right to Dream and Diambars are among those that emphasize the importance of providing quality academic education to their talents alongside technical sportive skills, in order to open other doors besides football for them. Founder of Right to Dream – a non-profit talent academy that holds the ownership of the Danish Superliga Club FC Nordsjaelland (FCN) – Thomas Vernon, mentioned in an interview with Thomson Reuters Foundation that their “ambition is that kids can drop into societies around the world and have other strings to their bow.” Similarly, former football player and the Chief Executive of Diambars Institute Jimmy Adjovi-Boco mentions that “when they arrive at 13 years old at the institute, there are some young people who cannot read or write” and he emphasizes that their “goal is to help them progress academically and that they come out at 18 with a future, other than football if they do not manage to find a place in the community.”

European Clubs Being Transformed by African players: interdependence

Some of the alumni of these talent academies become key components of clubs around the world, including those whose names are known to everyone. Yaya Toure of Barcelona was once a young player in ASEC Mimosas, Samuel Eto’o of Barcelona was training in Kadji Sports Academy in Cameroon, Idrissa Gueye of PSG was like the current talents in Diambars, and Sadio Mané of Bayern Munich and Habib Diallo of RC Strasbourg Alsace were once a part of Generation Foot, just to name a few past and present athletes.

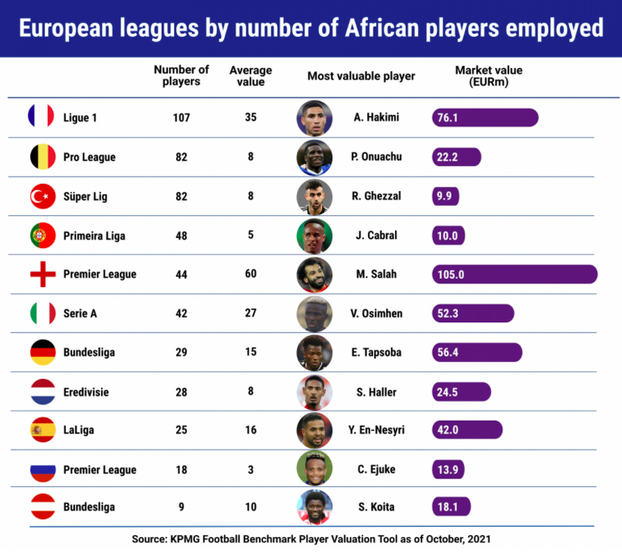

The top five European leagues that employed the greatest number of African players in 2021 were Ligue 1, Pro League, Turkish Super Lig, Primeira Liga, and Premiere Ligue with 107, 82, 48, 48, and 44 players respectively according to KPMG. This shows how African players are integral to the running and success of the clubs competing in those leagues. It is no surprise that during the Africa Cup of Nations (AFCON) there was a great amount of worry, especially in Belgian and French teams like PSG, Angers, and Olympique Lyonnais, because they were sending off some our their most important talents to play for their national teams during the season.

It is just clear that the talent academies in Africa are here to stay and probably to develop and grow further. Hopefully, more and more will adopt a more well-rounded approach to the training of their talents by incorporating quality academic programs. With more players coming out of these programs, some staying in their homelands playing for local clubs, some moving overseas to be a part of teams there, and others pursuing careers in different fields, such talent academies can be a component of the intricate process of progress and development in the continent.

By Ece Ağalar